The way we spell and pronounce parts of a word in English often comes down to the digraph(s) it contains.

These digraphs are present in the words we use every day. The ch in cheese, ea in bread, or the kn in knee are digraphs.

But what exactly is a digraph? The concept is too small to explain in the intro, so you’ll have to read the entire article.

By the end of this article, you’ll know what digraphs are in their entirety, how to teach them, and spot them in a sea of sounds.

Key Takeaways

- A digraph is a pair of letters that represents a single sound.

- There are two main types: consonant digraphs and vowel digraphs.

- Silent digraphs don’t contribute to pronunciation but still appear in spelling (think: gn, kn, mb).

- Digraphs are introduced early in literacy education, usually around age five.

- Learning to read and spell with digraphs takes repetition, exposure, and the occasional reminder that English doesn’t always follow its own rules.

Let’s begin.

Definition of a Digraph

A digraph is when two letters come together and make a single sound.

It might look like a regular pair of letters at first, but they don’t behave like individual sounds anymore.

The sound made by a digraph is often different from the sounds you’d get if you read the two letters separately.

Never Worry About AI Detecting Your Texts Again. Undetectable AI Can Help You:

- Make your AI assisted writing appear human-like.

- Bypass all major AI detection tools with just one click.

- Use AI safely and confidently in school and work.

Take “sh” in ship. Individually, “s” sounds like /s/ as in sun, and “h” sounds like /h/ as in hat. But together, they don’t keep their original sounds. Instead, “sh” forms a new one, /sh/, which is a completely different phoneme.

But of course, English being English, the above is not always the case.

We have many digraphs that make the sound of one of the two letters forming that digraph.

The “ck” in brick, for example, makes the same /k/ sound you’d hear in cat or kite. It still counts as a digraph, though, because those two letters are working together to make just one sound.

Now, digraphs are usually split into two major groups: consonant digraphs and vowel digraphs.

When both letters in the pair are consonants, like “ch” or “ck,” we call them consonant digraphs. When the pair is made of vowels, say “ai” or “ea”, they’re called vowel digraphs or vowel teams.

Approximately, written English includes more than 125 digraphs. Around 75 of those are consonant digraphs, and about 50 are vowel digraphs.

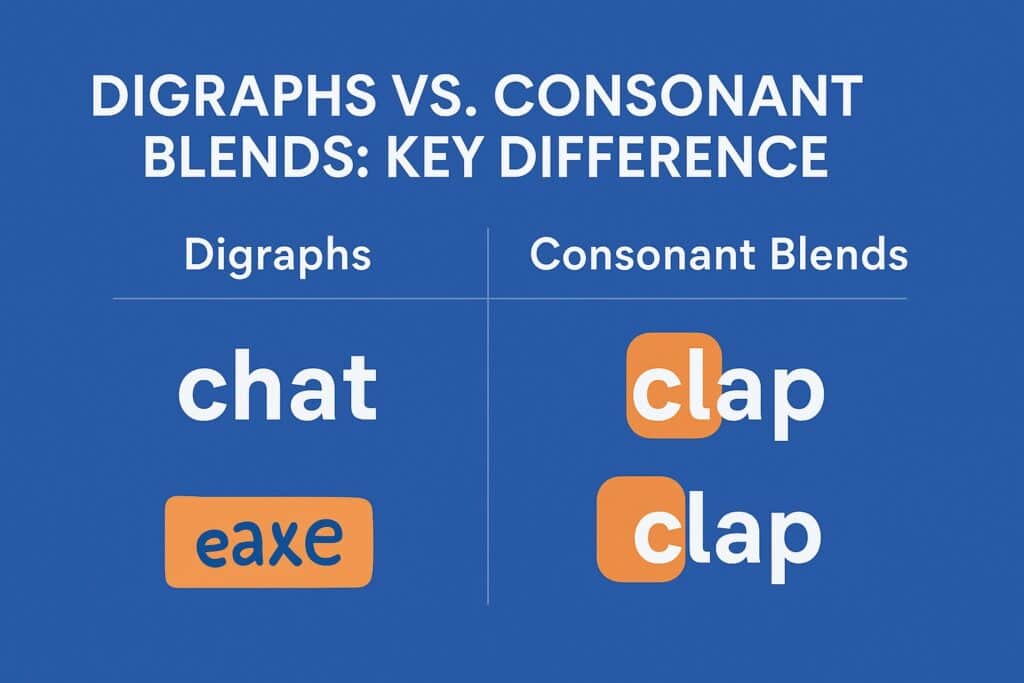

Digraphs vs. Consonant Blends: Key Differences

There’s another concept in English called blends.

A blend is made up of two or more consonants, where each letter keeps its original sound. You can still hear each one clearly when the word is spoken.

The biggest difference between blends and digraphs comes down to how the sounds work.

Take a word like clap.

The letters “c” and “l” come right next to each other, but they don’t lose their identities. “C” sounds like /k/ and “l” sounds like /l/, just like they do in cat and log.

So this blend of “cl” is what we call a consonant blend.

Now compare that to a word like chat. The “ch” here doesn’t split into a /k/ and /h/ sound. Instead, it forms a new sound altogether, /ch/. That makes it a digraph, because both letters combine to represent one phoneme.

It’s not always black and white like this, though. Some combinations can behave differently depending on where they show up in a word.

For instance, the letters “ng” usually form a digraph. In words like ring, long, or bang, you don’t hear a clear /n/ followed by a /g/. Instead, it’s one blended sound, /ŋ/.

However, that changes when “ng” falls between syllables in longer words. If you say danger or fungi out loud, you can pick out the /n/ and /g/ sounds separately. In those cases, “ng” is acting more like a blend than a digraph.

For students working on school projects, the Ask AI tool by Undetectable AI can be a helpful companion. It can help in breaking down concepts like this clearly and quickly.

And if you’re ever unsure about sentence structure, spelling, or grammar along the way, our built-in Grammar Checker can help smooth things out.

Common Consonant Digraphs

Remember the consonant digraphs (two consonants making a single sound) you read about above?

Here’s a digraphs list covering several consonant digraphs (not all) with their examples and the sound they make:

| Digraph | Phoneme (IPA) | Sound | Examples | Pronunciation Tips |

| bb | /b/ | “b” as in bat | bubble, ribbon, hobby | Doubled “b” retains a strong /b/ sound. |

| bt | /t/ | “t” as in top | debt, doubt, subtle | Silent “b” (only the /t/ is pronounced). |

| cc | /k/ | “k” as in kite | account, accuse, soccer, hiccup | Usually before “a,” “o,” “u” (hard /k/ sound). |

| ch | /tʃ/ | “ch” as in chip | chair, cheese, church | Most common “ch” sound. |

| ch | /k/ | “k” as in kite | school, chaos, chord, anchor | Found in Greek-derived words. |

| ch | /ʃ/ | “sh” as in shoe | chef, machine, champagne | French/Loanword pronunciation. |

| ci | /ʃ/ | “sh” as in shoe | special, delicious, ancient | Typically before “-tion” or “-ous.” |

| dg | /dʒ/ | “j” as in jump | judge, bridge, fudge, dodgy | Often followed by silent “e.” |

| gh | /g/ | “g” as in goat | ghost, spaghetti, ghoul | Only pronounced at the start of words. |

| ll | /l/ | “l” as in lip | ball, pull, hello | Doubled “l” keeps a clear /l/ sound. |

| mb | /m/ | “m” as in map | comb, thumb, climb | Final “b” is silent. |

| mn | /m/ | “m” as in map | autumn, column, hymn | Final “n” is silent. |

| ng | /ŋ/ | “ng” as in sing | ring, strong, finger | Nasal sound; avoid adding a /g/ after. |

| ph | /f/ | “f” as in fish | phone, dolphin, graph | Always represents /f/ (Greek origin). |

| ps | /s/ | “s” as in sun | psalm, psychology, pseudonym | Silent “p” (Greek-derived words). |

| rh | /r/ | “r” as in red | rhyme, rhythm, rhinoceros | “h” is silent (Greek origin). |

| sc | /s/ | “s” as in sun | science, scene, scissors | Before “e,” “i,” or “y.” |

| th | /θ/ | Unvoiced “th” as in think | thin, math, bath | No vocal cord vibration (soft sound). |

| th | /ð/ | Voiced “th” as in this | that, mother, smooth | Vocal cords vibrate (harder sound). |

| th | /t/ | “t” as in top | thyme, Thailand, Thomas | Rare exceptions (names/loanwords). |

| sh | /ʃ/ | “sh” as in shoe | ship, wish, fashion | Always the /ʃ/ sound. |

| wh | /w/ | “w” as in wet | when, whale, wheel | Standard pronunciation. |

| wh | /h/ | “h” as in hat | who, whole, whose | Only in some words |

Common Vowel Digraphs

I briefly touched on vowel digraphs earlier. Let’s look more closely at them now.

For a recap, a vowel digraph is where the combined letters represent a single vowel sound.

Typically, a vowel digraph involves at least one vowel letter.

For instance, in the word cow, the sound /ou/ is represented by a vowel-consonant pair.

The same goes for /oi/ in toy and /ar/ in dark. Each of these examples features digraphs that produce vowel sounds, even though they include consonants in the letter pair.

But this rule isn’t as cut and dry as it sounds.

You’ll come across vowel digraphs where both letters are vowels, either the same vowel or different.

Examples include ai in brain, ou in bounce, oo in book, ee in cheese, and many more.

Vowel digraphs often appear in the middle of words, but that’s not a strict rule either. They can also appear in the beginning (ooze) and at the end (blue).

Here’s a digraphs list containing several vowel digraphs.

| Digraph | Phoneme (IPA) | Sound | Examples | Pronunciation Tips |

| ai | /eɪ/ | “ay” as in day | rain, paint, tail | Usually at the start/middle of words. |

| ay | /eɪ/ | “ay” as in day | play, stay, delay | Typically at the end of words. |

| ea | /iː/ | “ee” as in see | eat, tea, dream | Most common sound. |

| ea | /ɛ/ | “eh” as in bed | bread, dead, head | Less frequent; exceptions. |

| ee | /iː/ | “ee” as in see | see, tree, cheese | Always long /ee/ sound. |

| ie | /iː/ | “ee” as in see | thief, field, belief | Usually in the middle of words. |

| ie | /aɪ/ | “eye” as in sky | pie, die, lie | Often at the end of words. |

| oa | /oʊ/ | “oh” as in go | boat, coat, road | Always long /o/ sound. |

| oe | /oʊ/ | “oh” as in go | toe, hoe, foe | Usually at the end of words. |

| ue | /uː/ | “oo” as in moon | blue, clue, true | Often after “g” or “l.” |

| ui | /uː/ | “oo” as in moon | fruit, juice, suit | Common in multisyllabic words. |

| oo | /uː/ | “oo” as in moon | moon, spoon, food | Long /oo/ sound. |

| oo | /ʊ/ | “uh” as in book | book, foot, good | Short /oo/ sound. |

| ou | /aʊ/ | “ow” as in cow | out, house, cloud | Common in one-syllable words. |

| ou | /ʌ/ | “uh” as in cup | young, trouble, country | Exceptions in multisyllabic words. |

| ow | /aʊ/ | “ow” as in cow | cow, now, brow | Often at the end of words. |

| ow | /oʊ/ | “oh” as in go | snow, grow, slow | Less frequent; exceptions. |

| oy | /ɔɪ/ | “oy” as in boy | boy, toy, enjoy | Always at the end of syllables. |

| oi | /ɔɪ/ | “oy” as in boy | coin, voice, oil | Usually in the middle of words. |

Another important concept within this category is the split digraph.

Split digraphs involve two letters that represent a single vowel sound but are separated by a consonant.

The most common structure includes a vowel followed by a consonant, and then an “e” at the end of the word.

These are sometimes referred to as “magic e” or “silent e” words in early reading programs.

Consider the word rope. The vowel sound /oa/ is represented by the letters “o” and “e,” with the consonant “p” in between.

Similarly, kite contains the long /i/ sound created by the “i” and “e” pair, split by the consonant “t.”

There are six split digraphs in total, which are given below. However, some variations aren’t covered below.

Refer to this PDF of vowel digraphs for all regular vowel digraphs and split digraphs with all variations.

| Digraph | Phoneme (IPA) | Sound | Examples | Pronunciation Tips |

| a-e | /eɪ/ | “ay” as in day | ape, bake, came | Silent “e” makes the “a” long. |

| e-e | /iː/ | “ee” as in see | Eve, Pete, theme | Rare; often in Greek-derived words. |

| i-e | /aɪ/ | “eye” as in sky | bike, dice, hide | Silent “e” makes the “i” long. |

| o-e | /oʊ/ | “oh” as in go | bone, choke, home | Silent “e” makes the “o” long. |

| u-e | /juː/ or /uː/ | “yoo” or “oo” | cute (yoo), duke (yoo), mule (yoo), tube (oo) | Can sound like “yoo” or “oo.” |

| y-e | /aɪ/ | “eye” as in sky | byte, hype, type | Functions like “i-e”; common in tech terms. |

Silent Letter Digraphs

In the digraph lists above, you saw many digraphs where one letter was silent. Those were silent letter digraphs.

Silent letter digraphs pair a letter that is pronounced with another that remains silent.

The silent letter’s presence doesn’t affect pronunciation, though it may still influence the way the word is understood, especially in written form.

These silent letters often reflect the history of the language, in which case they show where a sound used to be pronounced but no longer is.

In the word knee, for instance, the combination “kn” forms a digraph where the k is silent. The result is that “kn” is pronounced simply as /n/. Similarly, in write, the “wr” digraph is pronounced as /r/, with the w being silent.

It’s also worth noting that some of these digraphs don’t always behave consistently. The “gn” digraph, for example, has a silent g in words like sign or align.

However, in words like signal or ignite, “gn” no longer remains a digraph because the g and n are split across syllables.

For reference, here’s a brief digraph list showing some of the most common silent letter digraphs, along with notes on what’s silent and how to identify them by sound:

| Silent Letter Digraphs | What’s Silent | Sound Tip | Examples |

| kn | k | Sounds like /n/ | knee, knock, know |

| wr | w | Sounds like /r/ | write, wrist, wrong. wrench |

| gn | g (in most cases) | Sounds like /n/, unless syllables split | gnome, sign, align |

| mb | b | Sounds like /m/ at the end of a word | comb, limb, numb |

| ck | No distinct silent letter, but forms one /k/ sound | Treat as a digraph for /k/ | kick, sock, luck |

For students or writers who want extra support breaking these patterns down or just need a quick explanation, Ask AI by Undetectable AI is the go-to tool to clear things up.

And for day-to-day spelling and writing tasks, the Grammar Checker can catch issues before they become problems.

Digraphs in Early Literacy

Now it’s worth looking at how digraphs are handled in early literacy, in case you’re reading this as a teacher or a parent homeschooling your kids.

Before children are taught any kind of digraph, they first need to have a solid grasp of individual letter sounds.

That means they should be able to recognize letters on sight and produce their corresponding sounds fluently.

On top of that, they should be able to blend and segment simple one-syllable words, typically following a consonant-vowel-consonant (CVC) pattern.

Skills like these lay the groundwork for understanding more complex sound combinations like digraphs.

The age at which digraphs are introduced can vary from one country to another, but in most cases, it starts early.

In England, for instance, children are usually introduced to digraphs during the academic year they turn five, which is when they enter reception.

In the United States, the timeline is fairly similar.

Children begin Kindergarten around the same age, and early digraphs are often introduced during that first school year.

Some of the earliest digraphs introduced in classrooms are double consonants like “ff,” “ll,” and “ss.”

These tend to show up during the first term in English schools and help ease children into the idea that two letters can work together to make a single sound.

As the term progresses, other common consonant digraphs such as “ch,” “sh,” and “th” are added into instruction.

Vowel digraphs tend to follow later in the term or in the following year as children gain more confidence with reading.

By the end of their reception year, many children in the UK will have encountered more than a dozen vowel digraphs.

As they transition into Year 1, typically around age six, they’re introduced to even more vowel and consonant digraphs.

As for split digraphs, since the letters are split up in the word, it can be harder for children to recognize them as a single sound unit.

Because of this, split digraphs are generally introduced only after a child has shown that they can confidently read and spell words containing regular digraphs.

For parents, teachers, or students who need extra support with this stage of learning, AI Chat by Undetectable AI can be a helpful tool.

It can generate word lists based on specific digraphs, create printable activities, or help with reading comprehension questions.

Here’s a detailed guide on teaching digraphs.

Digraph Word List by Grade Level

Kindergarten / Reception (Age 4–5)

| Digraph Type | Digraphs Introduced (sample) | Example Words | Notes |

| Consonant Digraphs | ff, ll, ss, zz, etc | puff, bell, mess, buzz | Often introduced early in the year. |

| Consonant Digraphs | ch, sh, th, wh, etc | chip, shop, this, when | Commonly taught mid-to-late term. |

| Vowel Digraphs | ai, ee, oa, etc | rain, feet, boat | Introduced toward the end of the year. |

| Vowel Digraphs | oo (long and short), etc | moon, book | Recognizing sound variation is key. |

Grade 1 / Year 1 (Age 5–6)

| Digraph Type | Digraphs Introduced (sample) | Example Words | Notes |

| Consonant Digraphs | kn, wr, gn, ph, mb, etc | knee, write, gnome, phone, comb | Builds on previous knowledge of silent letters. |

| Vowel Digraphs | ea, ie, ue, oo, ow, etc | leaf, pie, blue, spoon, snow | Digraphs appear in varied vowel sounds. |

| Vowel Digraphs | ar, or, ir, ur, er, etc | car, corn, bird, fur, her | Covers r-controlled vowels. |

| Split Digraphs | a-e, i-e, o-e, u-e, e-e, etc | cake, bike, rope, cube, these | Usually introduced after solid digraph grasp. |

Grade 2 / Year 2 (Age 6–7)

| Digraph Type | Digraphs Reviewed & Extended | Example Words | Notes |

| Consonant Digraphs | Extend use in multisyllabic words | graphic, whisper, chimney | Reinforces earlier learning in more complex words. |

| Vowel Digraphs | ow, ou, oy, oi, etc | cow, out, toy, coin | Focus on diphthongs and alternative spellings. |

| Split Digraphs | Review and apply in new contexts | flute, theme, shine | Introduced only after mastery of regular digraphs. |

Want to see our AI Detector and Humanizer in action? Check them out in the widget below!

Final Thoughts

Digraphs are a simple concept, but due to several types and variations of them, it takes time to learn them fully.

But once you understand how they work, you’ll spot them in just about every word you read.

And if you need help building custom word lists, printable activities, or planning a reading lesson around digraphs, Undetectable AI’s full suite of AI tools is at your service.