How much time would it take you to read 20 research papers?

1 hour each? Or 2?

Now imagine if you would have to read 50 papers. Suddenly, reading them all would feel extremely overwhelming.

This exact problem was faced by Murray Luck (a Stanford chemistry professor), back in 1931.

Every year, thousands of new studies were published, and scientists struggled to read and keep track of them all.

Luck knew something had to change. Instead of drowning in endless papers, he created a smart, clear summary that highlighted key findings, uncovered gaps, and saved countless hours for researchers.

This was the birth of the very first formal literature review—the Annual Review of Biochemistry.

Fast forward to 2025. Students everywhere now dive into literature reviews first when starting academic writing. It seems like the obvious choice.

Literature reviews look easier, quicker, and way less intimidating than wading through original research papers.

But is that really true?

In this blog, we’ll explore what literature reviews are, their types, how they’re structured, and a simple step-by-step guide to help you write one with confidence.

Let’s dive in.

What Is a Literature Review?

In research…

- “Literature” means all the studies, reports, books, and articles written by experts on a certain topic.

- “Review” means to look at something carefully and think about it.

A literature review is when you gather many studies, books, or articles about one topic—and try to understand what they all say together.

For example: If your topic is how social media affects teenagers’ sleep, you’d collect studies about social media use, teenage sleep patterns, and mental health—and then show how they all relate.

Never Worry About AI Detecting Your Texts Again. Undetectable AI Can Help You:

- Make your AI assisted writing appear human-like.

- Bypass all major AI detection tools with just one click.

- Use AI safely and confidently in school and work.

→ If no study has looked at how late-night TikTok scrolling impacts teenage sleep in rural areas, you might say, “This is the gap my study wants to fill.”

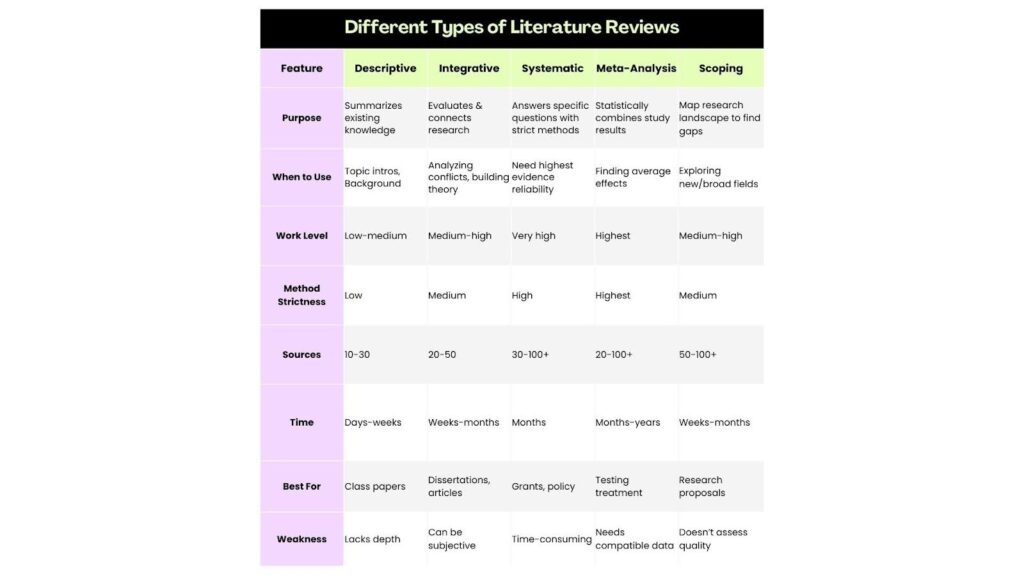

Types of Literature Reviews

There are different kinds of literature reviews, and each one works for different situations. Let’s discuss five types of literature reviews.

1. Descriptive Review

Descriptive review lists what the studies say, without asking too many questions. It is used when you’re just starting out and want to show what has already been said.

For example:

A review of studies (2010–2020) on social media’s impact on adolescent mental health reveals a predominant focus on anxiety and depression. While 60% of studies report negative correlations, 30% highlight neutral or positive outcomes, suggesting the need for nuanced frameworks.

→ Research intent: Exploratory—“Let’s see what’s been done.”

2. Integrative Review

Integrative review doesn’t just describe studies—it compares, questions, and connects them. You find patterns. You figure out what makes sense and what doesn’t.

Use it when you’re writing a thesis or a detailed academic essay, where you’re expected to form your own voice and argument.

For example:

An integrative review of 45 studies on workplace diversity (1995–2020) merges findings from surveys, case studies, and interviews. Themes like leadership inclusivity and intersectionality emerge, proposing a model for equitable organizational cultures.

→ Research intent: Argumentative—“This is what I believe, based on the evidence.”

3. Systematic Review

Systematic review is strict and rule-based. You follow a step-by-step method to find, choose, and judge studies. Use it when you’re doing high-level academic work, like a dissertation or a major research project.

For example:

A systematic review of 30 RCTs evaluates the efficacy of mindfulness-based therapy for chronic pain. Databases (PubMed, Scopus) were searched for peer-reviewed studies (2015–2022). Results show moderate pain reduction but highlight variability in intervention durations.

→ Research intent: Confirmatory—“Let’s make sure the results are strong and repeatable.”

4. Meta-Analysis

Meta-analysis is all about statistics. If you want to know what all the studies say on average, this is the way.

Use it when you have lots of similar studies with numerical results (like experiments), and you want to find the overall effect.

For example:

A meta-analysis of 20 studies (n=15,000 participants) compares CBT and pharmacotherapy for generalized anxiety disorder. Pooled effect sizes (Hedges’ *g*) indicate CBT’s superior long-term efficacy (*g* = 0.45, *p* < 0.01).

→ Research intent: Measurable impact—“Exactly how strong is the effect?”

5. Scoping Review

Scoping review doesn’t dig deep into each study. Instead, it maps the landscape—what’s been studied, where, and what’s still missing.

Use it when you’re planning a new research area or writing a grant proposal. It helps show where your work can make a difference.

For example:

A scoping review of AI ethics in healthcare (2015–2023) analyzes 120 articles. Dominant themes include algorithmic bias (40%), patient autonomy (30%), and regulatory challenges (20%), revealing a need for stakeholder engagement frameworks.

→ Research intent: Exploratory—“What’s out there, and where are the gaps?”

These were the different types of literature review. If you’re still confused, understand that it all comes down to your goal:

- If you want to explore: go Descriptive or Scoping.

- If you want to build an argument: choose Integrative.

- If you want solid proof: use a Systematic Review.

- If you’re chasing numbers: go with Meta-Analysis.

Look at these different examples of literature reviews:

→ Mobile-health: A review of the current state in 2015

→ Personal health records: A scoping review

→ Use of handheld computers in clinical practice: a systematic review

Structure of a Literature Review

Just like any writing, a literature review also needs a clear beginning, middle, and end. That’s where structure comes in.

Here is the most used structure of literature review:

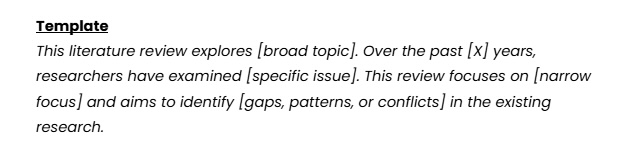

1. Introduction

This is where you explain what your review is about. It is like saying, “Here’s the topic, here’s why it matters, and here’s what I’m looking to find out.” Keep this section around 200-300 words.

2. Body

Here’s where you go into the details. You bring in different studies and organize them in a smart way. Keep this section around 800-1200 words. There are four different ways to do that:

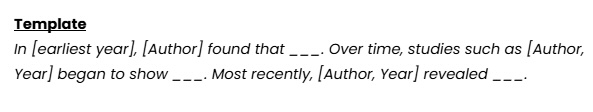

A. Chronological (by time)

Use this when you want to show how thinking or research has changed over time.

B. Thematic (by topic or theme)

Use this when there are different sides or themes to your topic.

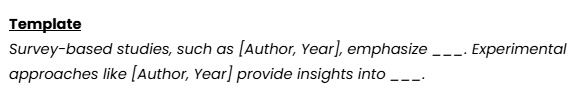

C. Methodological (by how studies were done)

Use this when you want to talk about the strengths or limits of the methods used.

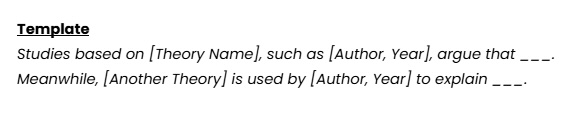

D. Theoretical (by the theory used)

Use this when your review involves deep or layered ideas.

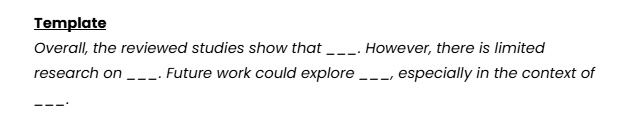

3. Conclusion

This is where you tie everything together. What do all these studies say together? What don’t they say? Where’s the gap—and how can your research help?

Step-by-Step Guide to Writing a Literature Review

Step 1: Define Your Topic and Scope

Ask yourself → What do I want to find out?

Start by writing a simple problem statement of your literature review — one or two lines about what’s bothering you or what you’re curious about.

For example: People in cities are struggling with climate change, especially flooding. How are they dealing with it?

You can use clear keywords to specify your topic, like:

→ “urban climate adaptation,” “coastal cities,” “flooding strategies.”

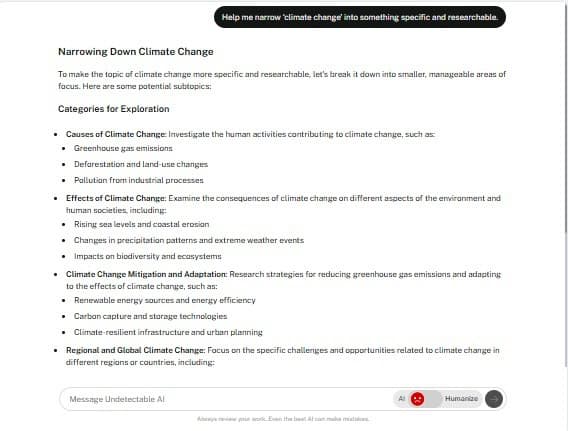

If your topic feels too big (like “climate change”)—use tools like AI Chat to narrow it down. Give this prompt to AI Chat:

→ Help me narrow ‘climate change’ into something specific and researchable.

It will give you a list of different sub-categories to explore. Once you get that, use the PICO Framework to specify your topic. For example:

- P – Population: Coastal cities

- I – Intervention: Urban adaptation strategies

- C – Comparison: Cities with vs. without these strategies

- O – Outcome: Reduced flooding damage

Scope Statement Example: This review will focus on urban adaptation strategies used by coastal cities from 2010 to 2024 to reduce flooding caused by climate change.

Avoid topics that are too wide (“climate change everywhere”) or too tiny (one city with no studies yet). You need just enough research to review.

Step 2: Search for Relevant Literature

Now it’s time to start with these reliable databases. Here are the top three databases to search for relevant literature:

- Google Scholar – free and good for a broad start

- JSTOR – for older, deep academic articles

- Scopus / PubMed – for science-heavy studies

When you’re searching, use Boolean logic. Boolean logic includes words like “AND” , “OR” and “NOT” etc. For example:

- “urban flooding” AND “climate adaptation” – gives you results that include both terms.

- “flooding OR stormwater” – shows results with either word.

- “climate change NOT agriculture” – removes results about farming.

Here’s a pro tip for you:

Find one good paper → look at its references → check who cited it → that’s citation chaining. It’s how you go deeper.

Step 3: Evaluate and Select Sources

Not all studies would be good. Some might be old. Some might be sketchy. Some say things that just aren’t true anymore.

So, how do you know which ones to keep? You need to look at five things:

- Is it useful for your topic? (Relevance)

- Who wrote it? Are they experts? (Author’s authority)

- How old is it? Is it still valid? (Publication year)

- Was it peer-reviewed? (That means other smart people checked it.)

- Is it from a trusted journal or just a blog?

The answer to all these questions need to be “YES.”

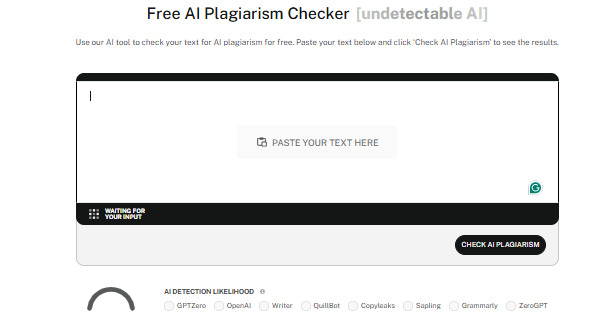

Now, with a high risk of plagiarism in recent academic papers, it’s important to ensure your summaries are both original and ethical.

Run your text through our free Plagiarism Checker tool to stay on the safe side.

Step 4: Organize Your Findings

By now, you’ve got a pile of sources. If you just stack them up and say “Here’s what this one said, and this one, and that one…” your review will feel like a mess.

Instead, you’ll need to organize all the data.

Group your data into patterns.

You can organize by:

- Theme (e.g., causes of stress, effects of stress)

- Method (surveys, interviews, lab studies)

- Theory (psychology models, economic theories)

I – Use the Synthesis Matrix

This is a table where you write topics across the top and sources down the side. You fill in who said what under each theme.

| Theme | Study A | Study B | Study C |

| Mental Health | Yes | Yes | No |

| Urban Planning | No | Yes | Yes |

Color-coding, labeling, and using sticky notes will ease your interpreting process. They will help you make sense of the big picture.

Step 5: Start Writing

Now comes the hard part—but also the most satisfying one: writing the literature review. Here’s how to do that, section by section:

1. Abstract

Write the abstract of literature in the last. Summarize your topic, scope, findings, and key gaps in 4–5 sharp sentences.

- Use exact language—cut filler.

- State what your review does, not what it “discusses.”

- No new information or citations.

Use the “one-sentence-per-element” method:

1 sentence for topic, 1 for scope, 1–2 for findings, 1 for gaps/future direction.

2. Introduction

In the introduction of literature review, you need to prove relevance and hook your reader immediately.

- Lead with a tension: stat, contradiction, or knowledge gap.

- Clearly define your focus.

- Frame the gap as an opportunity.

- End with a thesis: what your review will show or argue.

Treat the intro as the pitch to your research audience. You’re framing the problem they’ll care about.

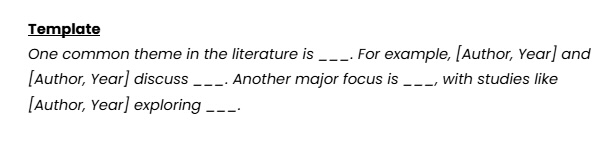

3. Body

In the body of literature review, avoid being a narrator of what each author said. You’re here to analyze, not annotate.

- Organize by theme, method, theory, or chronology—based on what best supports your point.

- Connect sources—compare, contrast, analyze patterns.

- Example: “Study X found…” to “Multiple studies indicate… however, emerging work challenges this…”

- Limit direct quotes. Paraphrase often—but deeply.

- Close each paragraph with insight, not a citation.

4. Conclusion

In the conclusion of literature review, wrap with purpose, not summary.

- Highlight the field’s consensus, tensions, and blind spots.

- Emphasize what’s missing—and why it matters.

- Point to next steps or implications.

Don’t just point out a gap—indicate the cost of not addressing it. Make it matter.

Writing Tips

- 70/30 Rule: 70% your own synthesis, 30% citations

- Don’t stack sources: Avoid “Author A said… Author B said…”

Use citation tools: Zotero, Mendeley, EndNote

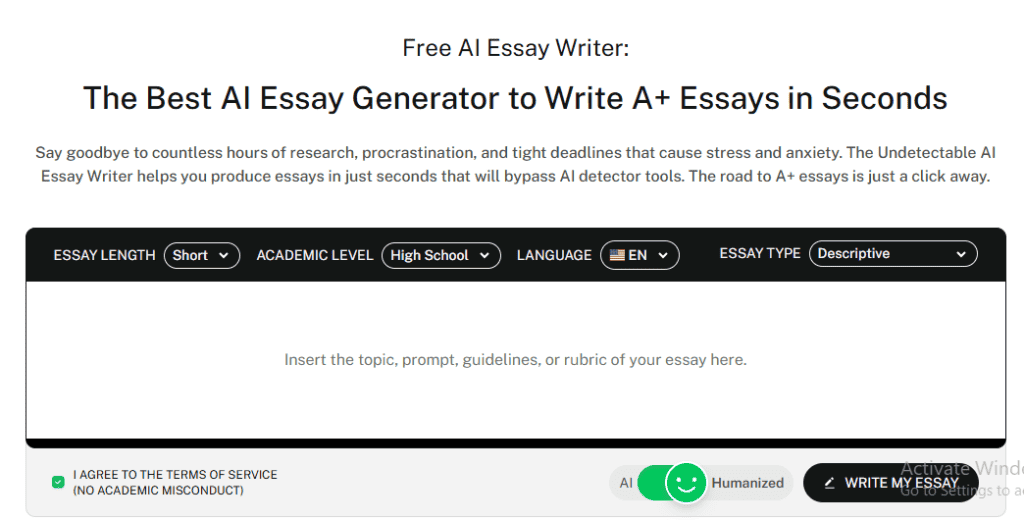

- Use AI writing assistants:

The Free AI Essay Writer helps you overcome research overload, procrastination, and the pressure of tight deadlines.

Here’s how to make the most of it:

- Step 1: Customize Your Essay Parameters

- Enter your topic, preferred word count, and writing style.

- Step 2: Generate a Draft in Seconds

- Once set, click “Write Essay.” Within moments, you’ll have a structured, factually accurate draft.

- Step 3: Refine and Finalize

- Review the structure, polish the arguments, and add your unique voice.

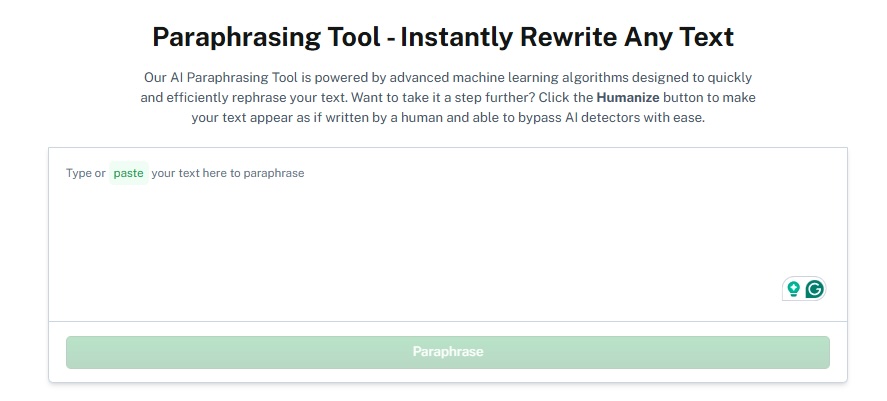

To ensure your analysis of complex theories doesn’t come across as stiff or mechanical, our Paraphrasing Tool serves as an essential bridge for articulating research “gaps.”

By leaning on this tool, you can translate dense academic jargon into sharp, high-impact statements that clearly prove the value of your own work within a persuasive conclusion.

Step 6: Final Review and Editing Tips

You’re almost done. But don’t submit yet—revise.

Part 1: Here’s your final checklist to revise your literature review:

- Is my tone academic and fair?

- Did I use transitions like “However,” “In contrast,” “Similarly”?

- Are my themes grouped in a way that makes sense?

If yes, move on to the second step of revision.

Part 2: Read it out loud.

- If it sounds boring or robotic, it probably is.

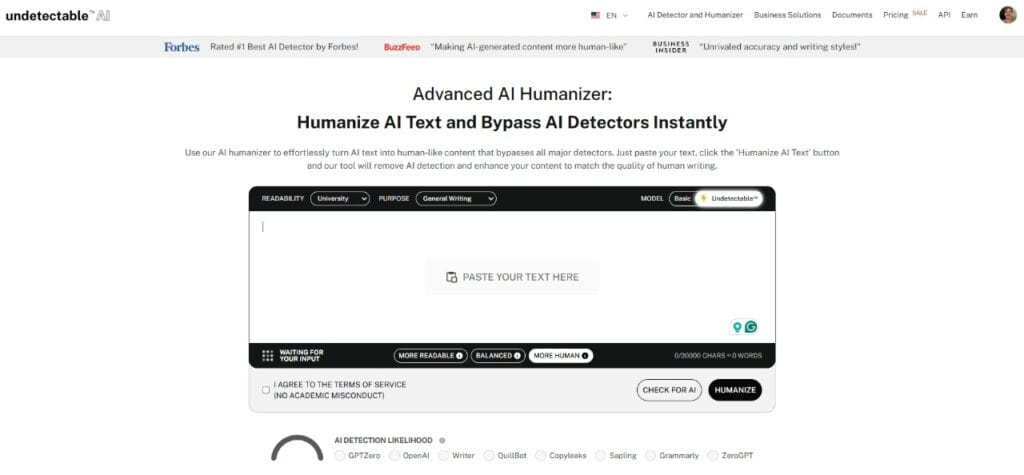

Part 3: Use the AI Humanizer

AI Humanizer rewrites stiff lines to sound clear, smart and in a humanized way. This tool will help you turn your AI text into human-like content that bypasses all major detectors.

For example:

- Before: This paper is about studies which were done in 2004.

- After: The early 2000s saw foundational studies that explored…

Test our AI Detector and Humanizer now using the widget below!

Conclusion

Writing a literature review doesn’t have to feel like climbing a mountain in the dark. It’s one of the easiest forms of academic writing.

Once you understand the structure—and see a few good examples— you’ll start getting it.

In literature reviews, you don’t just summarize. You connect the dots, question trends, and build a strong foundation for your own research.

Ask yourself:

- What are the recurring themes in the studies I’ve read?

- Are there gaps or contradictions that stand out?

- What does this body of work mean for my topic?

And most importantly:

What am I trying to say with all of this? That’s the core of a great literature review.

If you need help, use our free Essay Writer, and AI Humanizer to write and polish your draft into natural, readable prose.

Now the only question left is: Coffee first, or outline first?