Sonnet is a poetic form practiced by legends like Shakespeare, Petrarch as well as giants before and after them.

Do you want to try your hand at it, too? You’re warmly welcomed.

With the right guidance, you can also master this art. And that right guide is here.

This guide walks you through how to write a sonnet from start to finish.

You’ll also learn a lot more about different aspects of sonnets.

Let’s start with a sonnet-y beginning.

Come, learn the craft where language finds its soul,

Where fourteen lines can make a poet whole

What Is a Sonnet?

A sonnet is a 14-line poem, traditionally written in iambic pentameter.

The 14 lines are usually divided into quatrains (four-line stanzas) and usually a couplet.

But this varies from poet to poet. It has a specific rhyme scheme at the end of each line.

Never Worry About AI Detecting Your Texts Again. Undetectable AI Can Help You:

- Make your AI assisted writing appear human-like.

- Bypass all major AI detection tools with just one click.

- Use AI safely and confidently in school and work.

And as is the case with poetry, sonnet themes typically revolve around romantic love.

But now, almost any subject gets a pass.

Sonnets originated in Italy from Italian literature. Francesco Petrarch is one of the earliest and most famous practitioners of sonnets in the Italian language.

English poets later borrowed the discipline and poets like Henry Howard and Shakespeare had a major role in popularizing them.

As for the etymology of the word, “sonnet” it comes from the Italian “sonetto” which translates to “little song.”

Take a trip down memory lane, and perhaps you’ll recall Shakespeare’s Sonnet 18 from your school curriculum.

It’s arguably the most iconic sonnet of all time.

Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?

Thou art more lovely and more temperate:

Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May,

And summer’s lease hath all too short a date

Captivating, isn’t it? And that was just the beginning quatrain.

Notice how the endings of alternating lines match in rhyme.

This is one of the several rhyming schemes Shakespeare uses.

While learning how to write a sonnet in later sections, you’ll come across a few styles of writing a sonnet repeatedly.

So let’s explain and get it out of the way.

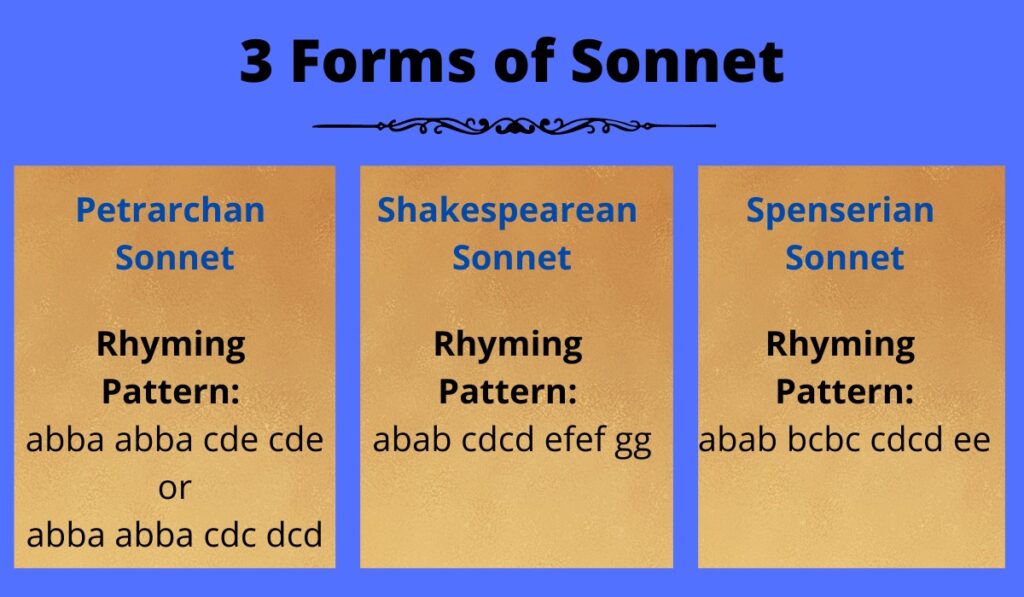

Different Types of Sonnets

Source: Swagatika Kar

Though all sonnets share core characteristics, they come with unique structural and thematic elements.

These variations are named after famous poets who developed their own style and set of rules.

Here are the three most recognized styles of sonnets.

1. Shakespearean

The Shakespearean sonnet, also known as the English sonnet, is structured into three quatrains followed by a closing rhymed couplet.

It adheres to a strict ABAB CDCD EFEF GG rhyme scheme (indicated in the sonnet below).

Each quatrain introduces a new aspect of the theme, while the final couplet often delivers a twist or resolution.

Shakespearean sonnets frequently explore themes of love, time, beauty, and mortality.

Take Sonnet 130, for example.

Rather than idealizing beauty, Shakespeare humorously subverts conventional love poetry:

Q1:

My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun; (a)

Coral is far more red than her lips’ red; (b)

If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun; (a)

If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head. (b)

Q2:

I have seen roses damask’d, red and white, (c)

But no such roses see I in her cheeks; (d)

And in some perfumes is there more delight (c)

Than in the breath that from my mistress reeks. (d)

Q3:

I love to hear her speak, yet well I know (e)

That music hath a far more pleasing sound: (f)

I grant I never saw a goddess go, (e)

My mistress, when she walks, treads on the ground: (f)

C:

And yet, by heaven, I think my love as rare (g)

As any she belied with false compare. (g)

The blunt, even ironic tone makes the Shakespearean sonnet as much a medium for wit as it is for deep reflection.

2. Petrarchan

The Petrarchan, or Italian sonnet, is divided into two sections.

First is an octave (eight lines) with an ABBA ABBA rhyme scheme, second is a sestet (six lines) that can have varying patterns such as CDE CDE or CDC DCD.

The turning point, or “volta,” between the octave and sestet marks a shift in perspective, argument, or emotional tone.

Petrarchan sonnets traditionally explore unrequited love, admiration, and philosophical musings. Take Petrarch’s own Sonnet 90:

O:

Upon the breeze she spread her golden hair (a)

that in a thousand gentle knots was turned (b)

and the sweet light beyond all radiance burned (b)

in eyes where now that radiance is rare; (a)

and in her face there seemed to come an air (a)

of pity, true or false, that I discerned: (b)

I had love’s tinder in my breast unburned, (b)

was it a wonder if it kindled there? (a)

S:

She moved not like a mortal, but as though (c)

she bore an angel’s form, her words had then (d)

a sound that simple human voices lack; (e)

a heavenly spirit, a living sun (c)

was what I saw; now, if it is not so, (d)

the wound’s not healed because the bow goes.. (e)

3. Spenserian

The Spenserian sonnet gets its name from Edmund Spenser.

It follows a more interwoven rhyme scheme: ABAB BCBC CDCD EE.

This linking pattern creates a smooth flow from one quatrain to the next.

While thematically similar to the Shakespearean form, Spenserian sonnets often emphasize storytelling and progression of thought.

A great example is from Spenser’s own “Amoretti”:

Q1:

One day I wrote her name upon the strand, (a)

But came the waves and washed it away: (b)

Again I wrote it with a second hand, (a)

But came the tide, and made my pains his prey. (b)

Q2:

“Vain man,” said she, “that dost in vain assay, (b)

A mortal thing so to immortalize; (c)

For I myself shall like to this decay, (b)

And eke my name be wiped out likewise.” (c)

Q3:

“Not so,” (quod I) “let baser things devise (c)

To die in dust, but you shall live by fame: (d)

My verse your vertues rare shall eternize, (c)

And in the heavens write your glorious name: (d)

C:

Where whenas death shall all the world subdue, (e)

Our love shall live, and later life renew.” (e)

Here, the Spenserian form reinforces the fleeting nature of time and human effort.

Notice how he weaves a flowing narrative that draws the reader along with it.

How Writing Sonnets Improves Your Writing Skills

Once you’ve learned how to write a sonnet poem, your command of language sharpens.

Writing sonnets trains your mind to think creatively within structured constraints.

You work within a set meter and rhyme scheme and develop discipline in word choice, sentence flow, and rhythm.

The challenge of fitting ideas into this framework pushes you to be concise while still conveying depth and meaning.

Additionally, sonnets improve your ability to recognize patterns in language.

The repetition of sounds and rhythms strengthens your grasp of phonetics. They attune you to the musicality of words.

Over time, this awareness influences your prose writing a lot.

Strategic poets often rely on our Paraphrasing Tool to refine the technical accuracy of their verse while keeping the emotional heart of the piece intact.

By using our platform to polish your phrasing, you can turn a rigid, “AI-sounding” draft into a memorable poem that resonates with your audience, free of any robotic or awkward syntax.

The Structure of a Sonnet

Every sonnet follows a set structure of the writer’s choice.

The structure remains consistent throughout the sonnet.

For ease in understanding how to write a sonnet poem for beginners in the later section, learning the structure is necessary.

Here are the elements that make a sonnet’s structure.

1. Understanding the 14-Line Format

The reason sonnets have 14 lines is largely due to tradition and effectiveness.

The structure creates a balance.

The length is enough to develop an idea but short enough to maintain intensity.

Most sonnets are divided into either two parts (as in the Petrarchan form) or four sections (as in the Shakespearean and Spenserian forms).

Each section serves a different purpose which you might have noticed reading the sonnets above.

One section introduces the idea, the subsequent ones expand on it until the sonnet ends with a resolution.

The final two lines in Shakespearean sonnets, called the couplet, often deliver a twist or epiphany.

2. The Role of Iambic Pentameter

Iambic pentameter is a rhythmic pattern in simple words.

An “iamb” consists of two syllables, with the first being unstressed and the second stressed (da-DUM).

“Pentameter” means there are five of these iambs in each line, totalling ten syllables.

For example, let’s go back to the first line of Shakespeare’s Sonnet 18:

/Shall I /compare /thee to /a sum/mer’s day?/

Note how each of the five pairs follows the unstressed-stressed pattern.

3. Rhyme Schemes Explained (ABAB, CDCD, EFEF, GG)

A rhyme scheme determines how the ending sounds of lines interact.

The Shakespearean sonnet follows the ABAB CDCD EFEF GG pattern, which structures thoughts into three quatrains followed by a punchy couplet.

Petrarchan sonnets, meanwhile, use ABBA ABBA for the octave (first 8 lines) and various patterns (CDE CDE or CDC DCD) for the sestet (last six lines).

How to Write a Sonnet Step by Step

It takes expertise and experience to come up with a single line of a couplet, let alone a sonnet.

But with a systematic approach, everything is possible.

I’ll introduce you to that very systematic approach and demonstrate it by creating a basic-level sonnet from scratch.

Let’s begin answering the big question: how to write a sonnet.

Step 1: Choosing a Theme or Subject

First, settle on a theme or subject that resonates with you.

Sonnets traditionally explore love, nature, time, and philosophical ideas.

However, now you can choose anything that stirs emotion or curiosity.

Whatever subject you choose, it must sustain development across fourteen lines.

For this demonstration, I’ll choose the theme of resilience in the face of adversity, a timeless topic with emotional depth.

Under this subject, I’ll be conveying how even in the darkest moments, there’s a spark of hope that keeps us going.

Step 2: Structuring Your Ideas into Quatrains and a Couplet

Once you have your theme, think about how to organize your ideas.

You need to shape your thoughts into the sonnet’s classic structure.

For example, if you’re here wanting to learn how to write a Shakespearean sonnet, it typically consists of three quatrains and a concluding couplet.

The first quatrain typically introduces the topic, and the second and third develop it further.

Finally, the couplet delivers the resolution in the form of a punchline, a revelation, or a moment of clarity.

I’ll divide my thoughts into this very structure:

- Quatrain 1: Describe the struggle or challenge.

- Quatrain 2: Show the emotional toll or despair.

- Quatrain 3: Introduce a shift—a glimmer of hope or strength.

- Couplet: Deliver a resolution or insight about resilience.

Step 3: Writing in Iambic Pentameter

Now tackle the rhythm, specifically, iambic pentameter.

Each line demands ten syllables alternating between unstressed and stressed beats: da-DUM da-DUM da-DUM da-DUM da-DUM.

The phrase “to BE or NOT to BE” follows this pattern.

Let’s draft our first quatrain in iambic rhythm:

- The storm has raged for days, its wrath unkind,

- The winds have torn the branches from the trees.

- The sky, a shroud of gray, has left me blind,

- And yet, within, a spark defies the breeze.

One way to practice iambic pentameter is by reading classic sonnets aloud to internalize the beat.

Your ear often catches rhythmic flaws your eyes miss.

Then experiment with simple lines.

Step 4: Perfecting the Rhyme Scheme

Go back to the types of sonnets and choose a rhyme scheme that appears the easiest.

Each quatrain must introduce new rhymes while maintaining a structured sound.

To make this work, choose words with flexible rhyme options and be open to slight rewording if needed.

Position your strongest rhyming words at quatrain ends for maximum impact.

You might have already seen in the first quatrain that I chose the Shakespearean rhyme scheme (: ABAB CDCD EFEF GG.)

The first quatrain followed ABAB. Here’s the second quatrain (CDCD):

- My heart, a fragile thing, has borne the weight,

- Of endless nights that stretched into the dawn.

- Each step I took, it seemed, would seal my fate,

- And yet, I found the strength to carry on.

Step 5: Adding Figurative Language and Poetic Devices

Layer in metaphors, similes, and sensory details that illuminate your theme.

If our theme was love, we could compare it to a flame that “flickers but never dies.”

In addition, integrate alliteration and assonance to make readers experience your poem in every way.

Each device should serve your theme rather than merely decorate.

For the third quatrain, I’ll introduce a shift in tone:

- Like roots that grip the earth through storm and strife,

- Or embers glowing faintly in the night,

- The will to live persists, the spark of life,

- A quiet force that bends but won’t take flight.

Finally, I’ll tie the theme together with a powerful couplet.

- So though the storm may rage and skies may weep,

- The heart endures—its promise it will keep.

Step 6: Revising and Polishing Your Sonnet

Once your first draft is complete, step back and read it aloud with fresh eyes.

Listen for awkward phrasing, uneven rhythm, or clunky rhymes.

Check each quatrain’s contribution to your theme’s development.

You may also consider alternate word choices, even for lines that seem finished.

Sharing your draft with others is also a good way to highlight areas for improvement.

Common Challenges in Writing a Sonnet (And How to Overcome Them)

Writing a sonnet isn’t easy, no doubt there.

Even seasoned poets stumble over its intricate demands.

Therefore, you, too, will face challenges despite knowing how to write a sonnet step by step.

But fear not.

Let’s make the challenges an opportunity to grow by learning how to tackle them head-on.

1. Struggling with Iambic Pentameter

For many beginners, the iambic pentameter is the biggest stumbling block.

Keeping a steady rhythm of alternating unstressed and stressed syllables can feel unnatural at first.

The trick is to speak naturally and then adjust.

Record yourself reading.

Most people naturally speak in near-iambic rhythms without realizing it.

Many everyday phrases already follow this pattern (e.g. I LOVE my DOG).

2. Finding the Right Words for the Rhyme Scheme

Force a rhyme, and your sonnet becomes a linguistic contortion.

The solution is to create lists of potential rhymes for key theme-related words.

But keep in mind that meaning should always come first.

Here’s where our AI Chat can suggest alternatives you might never conceive by yourself.

3. Keeping the Poem Meaningful While Sticking to the Rules

It’s easy to get so caught up in structure that the meaning of the poem gets lost.

Technical constraints can suffocate, meaning if you’re not careful.

If a line feels forced just to fit the rules, reconsider the idea rather than just the wording.

Let the structure serve your message, not the other way around.

In other words, you may break a rule slightly if doing so helps with the expression.

Examples of Famous Sonnets

Sonnets have been a beloved form of poetry for centuries, with some becoming timeless masterpieces.

Here are two renowned sonnets from two different eras.

The first one is from the Bard himself.

Sonnet 116, first quatrain:

Let me not to the marriage of true minds

Admit impediments. Love is not love

Which alters when it alteration finds,

Or bends with the remover to remove.

Notice how Shakespeare uses metaphors (the marriage of true minds) and a declarative tone to assert love’s constancy.

The next sonnet is from the 20th century, Edna St. Vincent Millay’s work.

What lips my lips have kissed, and where, and why,

I have forgotten, and what arms have lain

Under my head till morning; but the rain

Is full of ghosts tonight, that tap and sigh

The poet here looks back at her relationships and sighs in regret.

How to Ensure Your Sonnet Is Unique

With so many sonnets written throughout history, how can you ensure yours doesn’t blend into the background?

Here’s how to write a sonnet that’s unique besides strictly following the rules:

1. Avoid Clichés and Overused Phrases

Certain phrases have lost their spark through overuse.

These phrases frequently appear in love and nature themes.

Romantic sonnets also overflow with tired imagery: roses, hearts, moonlight. And just like poetry can feel repetitive, AI-generated visuals are everywhere too. That’s why tools like AI Image Detector help separate real creativity from machine-made imitations.

So think hard and come up with new ways to express ideas.

Compare love to something unexpected, or describe the passage of time in a way that hasn’t been done before.

Draw from personal experience, not poetic postcards.

2. Use an AI Detector to Check for AI-Like Patterns

Human writing has nuances that AI often struggles to replicate. Instead, AI’s writing feels mechanical or formulaic.

To make sure your sonnet doesn’t feel artificial, you can run it through our AI Detector and Humanizer tool.

The tool will analyze your sonnet for patterns that scream “machine-written.”

It’ll also suggest a humanized sample of the text with better emotional depth and originality.

Sharing and Publishing Your Sonnet

Once you’ve written your sonnet, the next step is getting it out into the world.

Your easiest and most immediate option should be sharing it with trusted friends and writing groups for feedback.

When you’re ready to publish, consider the following options:

- Literary Magazines

- Online Platforms

- Poetry Competitions

If you’re tech-savvy, you can also start a blog or share your work on social media.

To make your poetry accessible to international readers without losing the artistry of your rhyme scheme, you can use our Translator.

It helps you accurately adapt the complex structure of your sonnet for different cultures, ensuring that your unique “little song” resonates just as clearly in a literary circle in Rome as it does in London.

Final Words

With that, you now know everything about how to write a sonnet.

While we haven’t left any stone unturned, it can still take you lots of practice to come up with your first sonnet.

So don’t be too hard on yourself.

Remember, even Shakespeare fudged it sometimes.

And if you ever need an extra hand, Undetectable AI is at your disposal.

Sign up for our advanced writing tools now.