Writing guides often say that your work should be clean, tight, and efficient, where every word should earn its place.

If you ask any professional writer, the golden rule has always been to write without fluff.

But sometimes, the most memorable writing breaks the rules on purpose.

There are moments when you need to say “free gift”, even though gifts are free. Or say “tiny little details” because it provides rhythm and more emphasis.

That’s not fluff, that’s the wonderful world of pleonasm. It’s a technique that involves repeating or adding words intentionally to add punch.

You’ve likely been using pleonasms your whole entire life without even knowing it. See what we did there?

Your whole life. Your entire life. Same thing, said twice, and yet it can feel right in context.

In this article, we’ll look at what pleonasms are, when to use them, and how to avoid making your writing sound like a redundant mess of unnecessary repetition (yes, that was intentional, too).

Key Takeaways

- Pleonasm uses extra words to create emphasis, rhythm, or emotional impact in your writing.

- Unlike accidental redundancy, pleonasm is a deliberate rhetorical device that serves a purpose.

- Common examples include “burning fire,” “past history,” and “close proximity.”

- Effective pleonasm enhances meaning, while ineffective pleonasm just clutters your writing.

- Context determines whether your pleonasm is brilliant emphasis or sloppy writing.

What Is Pleonasm?

Pleonasm may sound like a disease you’d catch from a public pool, but it’s actually a rhetorical device that’s been around since ancient Greece.

Writers use it. Speakers love it. Your grandmother probably drops pleonasms in casual conversation without thinking twice.

Pleonasm Definition

Pleonasm is the technique of using more words than necessary to express an idea.

Never Worry About AI Detecting Your Texts Again. Undetectable AI Can Help You:

- Make your AI assisted writing appear human-like.

- Bypass all major AI detection tools with just one click.

- Use AI safely and confidently in school and work.

Those extra words aren’t just sitting there taking up space but doing work to add emphasis, create rhythm, or make the phrase more memorable.

The word itself comes from the Greek “pleonasmos,” meaning excess or superabundance. It’s when you say “I saw it with my own eyes” instead of just “I saw it.”

Technically, all seeing happens with your own eyes. But adding those extra words makes someone feel like you actually witnessed something incredible.

Pleonasm operates in this strange space between error and artistry. Grammar checkers hate it and writing teachers warn against it, but the most compelling prose often embraces it.

Classic Examples of Pleonasm

Let’s look at some pleonasms you may have used or heard before:

- “Free gift” – All gifts are free by definition, but this phrase emphasizes the no-strings-attached nature of the offer.

- “Added bonus” – A bonus is already something added, but saying “added bonus” makes it feel even more special. It’s the cherry on top of the cherry on top.

- “End result” – Results come at the end. That’s what makes them results. But “end result” has that finality to it that “result” alone doesn’t quite capture.

- “Past history” – History is always about the past, but “past history” sounds more serious, more official, like something you’d hear in a documentary.

- “Advance planning” – All planning happens in advance. Yet “advance planning” suggests you’re really on top of things, not just winging it at the last minute.

- “Close proximity” – Proximity already means nearness, but “close proximity” feels closer somehow, like things are practically touching.

Notice a pattern? These phrases feel right even when they’re technically wrong. That’s the magic of pleonasm.

It works on an emotional level rather than a purely logical one.

Historical Background of Pleonasm

Ancient rhetoricians loved this stuff. They had names for everything, and pleonasm was considered a legitimate tool of persuasion.

Cicero used it. So did Quintilian. If you wanted to move an audience in ancient Rome, you needed to know how to deploy strategic redundancy.

Shakespeare was a pleonasm master. “With mine own eyes” appears throughout his plays.

He gave us “the most unkindest cut of all” in Julius Caesar, a double superlative that’s grammatically horrifying but dramatically perfect. Nobody remembers “the unkindest cut.”

They remember “the most unkindest cut.”

The King James Bible is loaded with pleonasms. “Ask, and it shall be given you.” “Freely ye have received, freely give.”

These phrases stick in your mind precisely because they use more words than strictly necessary. The repetition creates rhythm and emphasis that simpler constructions can’t match.

Modern advertising rediscovered pleonasm. “New innovation.” “Completely finished.” “Absolutely perfect.” These phrases shouldn’t work, but they do.

They make products sound more innovative, more finished, more perfect than the base words alone could manage.

Pleonasm survived through history because it works. If it were just sloppy writing, it would’ve died out centuries ago. Instead, it seems like every generation of writers rediscovers its power.

Why Writers Use Pleonasm

So why do writers deliberately add unnecessary words? What’s the point of being intentionally redundant?

- For emphasis. When you want readers to really get something, repetition helps. “I’m completely and utterly exhausted,” adds extra emphasis compared to “I’m exhausted.” The extra words pile on, making the exhaustion feel more real, more total, more impossible to ignore.

- Rhythm matters in prose. Sometimes a sentence needs those extra syllables to flow properly. “Repeat again” has a better cadence than just “repeat” in certain contexts. Your ear tells you when the rhythm is right, even if your brain knows the words are redundant.

- Emotional impact gets amplified. Pleonasm creates intensity. “Burning hot” is hotter than “hot.” “Freezing cold” is colder than “cold.” The redundancy itself becomes a form of emphasis that makes readers feel the temperature.

- Cultural expectations play a role. Some pleonasms are so common that removing them sounds weird. If someone offers you a “free gift,” saying “that’s redundant, all gifts are free” makes you sound nitpicky rather than clever.

- Character voice gets developed. A character who says “I saw it with my own two eyes” sounds different from one who says “I saw it.” Pleonasm can be a characterization tool, showing how someone thinks and speaks.

- Comedy often relies on pleonasm. Adding unnecessary modifiers creates humor. “Irregardless” isn’t a word, but characters who use it tell us something about themselves. “A small tiny little problem” is funnier than “a small problem” precisely because of the redundancy.

The key is intention. Good writers choose pleonasm deliberately and know exactly what those extra words accomplish.

Bad writers just throw words to increase their word count on the page without thinking about whether each one earns its place.

Pleonasm vs. Redundancy

But isn’t pleonasm just redundancy? Yes and no.

Redundancy is the broader category. It’s any time you repeat information unnecessarily. Pleonasm is a specific type of redundancy that serves a rhetorical purpose.

All pleonasms are redundant, but not all redundancy is pleonasm.

- Redundancy without purpose is just clutter. “The reason is because” should be “the reason is” or “because,” but not both. “At this point in time” should be “now.” These are verbal tics, not rhetorical devices. They make writing worse, not better.

- Pleonasm with purpose enhances meaning. “I saw it with my own eyes” emphasizes personal witness in a way that “I saw it” doesn’t. The redundancy does work.

Here’s a test: Can you remove the extra words without losing something important? If yes, it’s probably just redundancy. If no, you might be looking at effective pleonasm.

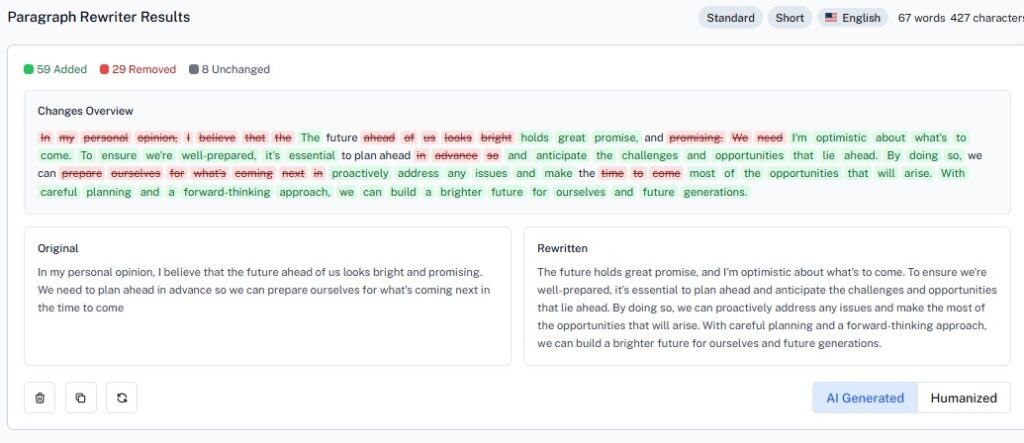

Let’s look at an example using Undetectable AI’s Paragraph Rewriter. Say you’ve written this overly redundant paragraph:

“In my personal opinion, I believe that the future ahead of us looks bright and promising. We need to plan ahead in advance so we can prepare ourselves for what’s coming next in the time to come.”

That’s a mess of redundancy with no purpose. Running it through a paragraph rewriter might give you:

“The future holds great promise, and I’m optimistic about what’s to come. To ensure we’re well-prepared, it’s essential to plan ahead and anticipate the challenges and opportunities that lie ahead. By doing so, we can proactively address any issues and make the most of the opportunities that will arise. With careful planning and a forward-thinking approach, we can build a brighter future for ourselves and future generations.”

See the difference? The rewriter strips out pointless redundancy (“personal opinion” is always personal, “future” is always ahead, “plan ahead” doesn’t need “in advance”) while potentially keeping effective pleonasm where it serves a purpose. “Plan ahead” could stay because the phrase has become idiomatic; it means something slightly different than just “plan.”

The goal isn’t to eliminate all redundancy but only to eliminate redundancy that doesn’t earn its keep and simultaneously enhance readability.

Common Mistakes When Using Pleonasm

Even intentional pleonasm can go wrong. Here are the biggest mistakes writers make:

- Overusing it turns everything into noise. If every other sentence contains pleonasm, nothing gets emphasized. The technique loses its power. Use pleonasm like a spice, where a little bit enhances the flavor and too much ruins the meal.

- Using pleonasm in formal writing often backfires. Academic papers and business reports need precision. “Advance planning” might fly in marketing copy, but “planning” works better in a project proposal. Know your audience and context.

- Stacking too many redundant phrases sounds ridiculous. “The final end result outcome” isn’t three times as emphatic as “the result.” Pick one pleonasm per idea and move on.

- Defaulting to clichéd pleonasms shows lazy thinking. “Added bonus” and “free gift” are so common they’ve lost their punch. If you’re going to use pleonasm, try to make it fresh. Find new ways to be redundant.

- Forgetting that different readers react differently. What sounds emphatic to one reader sounds stupid to another. Some people love “irregardless.” Others cringe at the very sound of it. Consider who you’re writing for.

- Mixing registers creates confusion. If you’re writing tight, minimalist prose, suddenly throwing in “completely and totally destroyed” breaks the established style.

The biggest mistake? Not making a conscious choice. Pleonasm works when you know you’re using it and why. It fails when it’s just verbal clutter that slipped past your editing process.

How to Use Pleonasm Effectively

So, how do you deploy pleonasm like a pro?

Here’s your game plan:

- Start by knowing the rule you’re breaking. You can’t use pleonasm effectively if you don’t understand why it’s technically redundant. Learn the grammar first, break it second.

- Use pleonasm sparingly for maximum impact. Think of it as a special effect. The first time Darth Vader shows up in Star Wars, it’s dramatic. If Darth Vader shows up every three minutes, it gets old. Same with pleonasm.

- Match pleonasm to character voice. A professor character probably won’t say “with my own two eyes,” but a grandmother character might. Let your characters’ speech patterns guide your choices.

- Read your work aloud. Your ear catches things your eye misses. If a pleonasm sounds natural when spoken, it’ll probably work. If it sounds clunky, cut it.

- Consider your genre. Comedy writing can handle more pleonasm than technical writing. Marketing copy uses it differently from literary fiction. Adjust your approach based on what you’re writing.

- Edit with purpose. When you spot a pleonasm in revision, ask: Is this doing work? Does it add emphasis, rhythm, or characterization? If yes, keep it. If no, cut it.

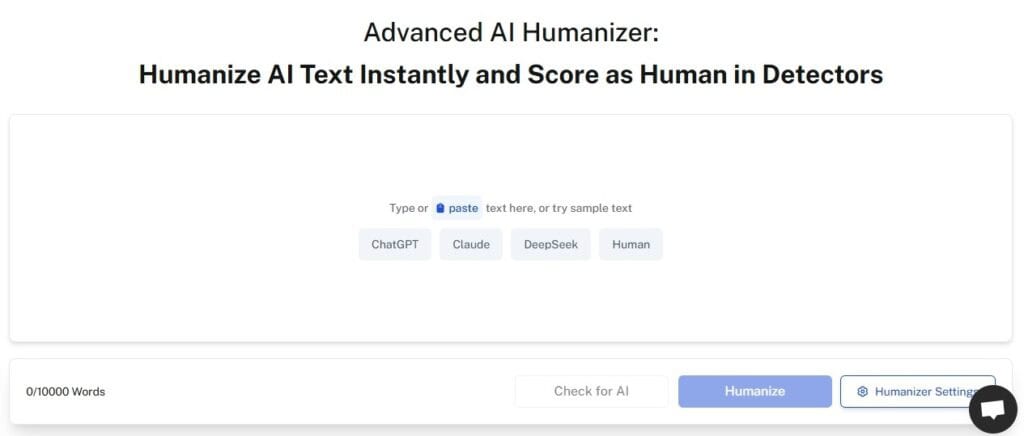

Tools like Undetectable AI’s AI Humanizer are particularly handy in these situations. Say you’ve written something that’s technically correct but sounds robotic:

“The plan requires preparation before implementation.”

That’s clean and clear, but it lacks personality. A humanizer might suggest:

“The plan requires advance preparation before we can actually implement it.”

Now you’ve got “advance preparation” (pleonasm) and “actually implement” (another subtle redundancy) that make the sentence sound more like something a human would say in a meeting. The redundancy adds natural rhythm and emphasis.

The key is making your pleonasm sound intentional, not accidental. Readers should feel the emphasis, not notice the technique.

Get started with our AI Detector and Humanizer in the widget below!

Say It Twice, Mean It Once

Pleonasm is one of those writing techniques that makes grammar purists lose their minds, but it evokes a sense in readers.

That’s the trade-off. You sacrifice technical correctness for emotional impact, rhythm, or emphasis.

Should you use it? Depends on what you’re writing and who you’re writing for. Business emails? Probably keep it minimal. Comedy sketches? Load up. Literary fiction?

Use it judiciously for character voice and key moments. Marketing copy? It’s practically required.

The most important thing is awareness. Know when you’re being redundant. Know why those extra words are there.

Make deliberate choices about every pleonasm that makes it into your final draft, and make sure every redundant word is there on purpose, doing real work, earning its place on the page.

That’s the secret to good pleonasm. It’s not about adding unnecessary words. It’s about adding necessary redundancy.

And once you understand the difference, your writing will be completely and totally transformed.

Ensure your writing stays natural and human with Undetectable AI.