You walk into a supermarket intending to buy a simple jar of pasta sauce. The first one you see costs $25, which is way out of your budget, but just a few steps later, you spot another one priced at $11.

And without much thought, you end up getting it, thinking it’s a reasonable deal, even though you’d have hesitated at paying that much for sauce in a different context.

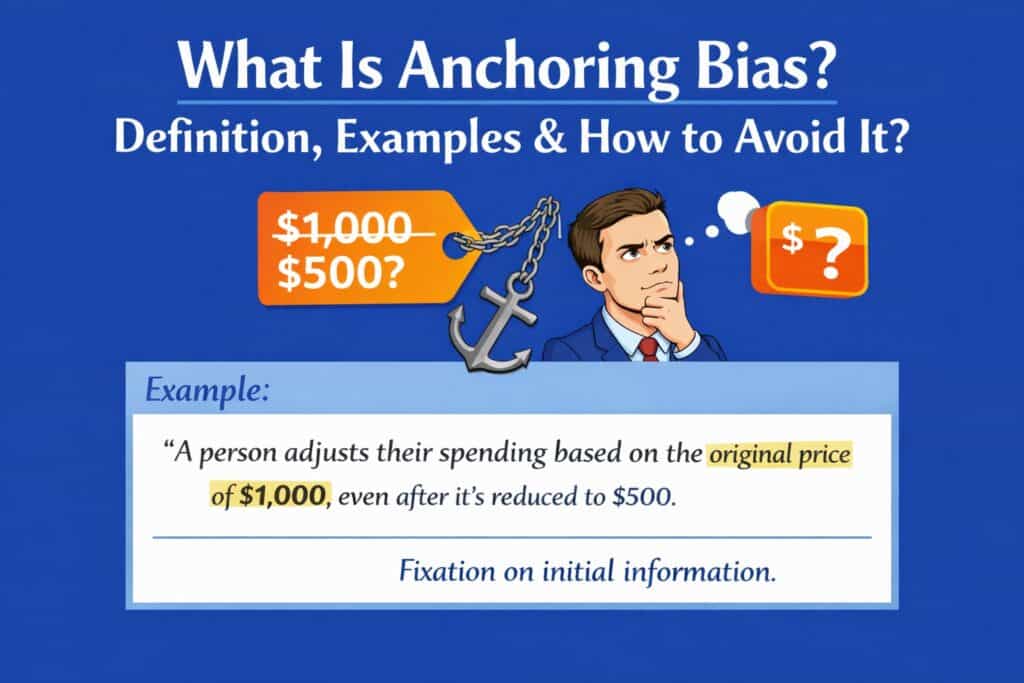

This is what researchers call anchoring bias, a cognitive problem where your decisions are based on the first piece of information you encounter.

The reason anchoring bias exists is that the human brain constantly tries to reduce decision fatigue and relies on shortcuts.

Anchoring makes your thought process faster, although more prone to poor decision-making too.

In this article, I’ll talk about what exactly is anchoring bias, why it occurs, how to recognize it, and what you can do to protect yourself from it.

Key Takeaways

- Anchoring bias is a cognitive bias which means that people rely too heavily on the first piece of information they encounter and use it as a reference point for all later judgments.

- Anchoring bias is explained by two main psychological mechanisms: confirmatory hypothesis testing and anchoring and adjustment.

- “Was/now” discounts in retail, salary negotiations, academic grading, and research estimates are some common examples of anchoring bias in everyday life.

- Although anchoring cannot be fully eliminated, we can reduce its influence on our decisions if we deliberately argue against the anchor and delay the exposure to anchor.

What Is Anchoring Bias?

Anchoring bias is a thinking mistake that defines how people rely too much on the first piece of information they get when making a decision.

That first bit of information, which could be an initial number or idea, is called the anchor.

You could say that the anchor becomes a reference point such that all future judgments stay close to it instead of being made from scratch.

Never Worry About AI Detecting Your Texts Again. Undetectable AI Can Help You:

- Make your AI assisted writing appear human-like.

- Bypass all major AI detection tools with just one click.

- Use AI safely and confidently in school and work.

What’s interesting is that anchoring bias affects our decisions even when the reference is wrong, even when we clearly know it’s wrong.

For example, if you see an item on sale that “used to cost $500” and is now $250, you think of $500 as the baseline, even if that item was never worth that much to begin with.

Anchoring bias was first introduced by the psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman. The duo used a series of deceptively simple experiments that ended up dismantling the myth that humans are rational decision-makers.

In one of the experiments, they gave the participants 5 seconds to estimate the answer to a math problem.

Half the participants were given this question: 1 × 2 × 3 × 4 × 5 × 6 × 7 × 8

And the other half got this: 8 × 7 × 6 × 5 × 4 × 3 × 2 × 1

It turned out the first group’s median estimate was 512 while the second group’s was 2,250. It naturally made the researchers wonder what caused the difference, because the problem was exactly the same, just arranged differently.

What happened was the difference in starting points. The first group began with small numbers, while the second group saw larger ones.

Once an anchor was established from the first few numbers, the brain adjusted close enough.

The experiments were replicated time and again, across different cultures, age groups, levels of expertise, occupations, etc, but it predicted judgements in similar ways.

Why Anchoring Bias Matters

The most immediate consequence of anchoring bias is numerical distortion as your values gravitate toward initial values.

The effect persists even when the anchor is:

- Random

- Obviously irrelevant

- Explicitly described as having no informational content at all

When researchers encounter ambiguous data, prior anchors in the form of previously established theories or benchmarks can affect their interpretation.

A study on legal decision-making found that highly deliberative decisions, such as quantifying damages or setting penalties, are also susceptible to anchoring.

Similarly, numerical anchors have an effect on the amount people are willing to pay or accept for certain products/services.

Common Examples of Anchoring Bias

Perhaps the most obviously visible example of anchoring bias is retail, as we discussed earlier.

Crossed-out prices, or “was / now” price tags on items put on ‘sale’ are very effective at capturing consumer’s attention.

The reason is that the original price becomes the anchor, regardless of the fact that it may not be realistically worth that much.

The discounted price feels more like a bargain since it is evaluated relative to the anchor and not on its own, as an absolute value.

A similar concept applies to salary negotiations. It goes both ways! An employer’s initial offer or a candidate’s expected range, any of the two can be the reference point around which the entire conversation that follows is based on.

Anchoring bias also exists in academics. The perceived quality of the first few sections of a paper, for example, can be the reference for later work to be judged relative to it.

How Anchoring Bias Works in the Brain

Before we talk about why anchoring bias happens, you need to understand that anchoring is a subconscious process. You don’t notice it happening.

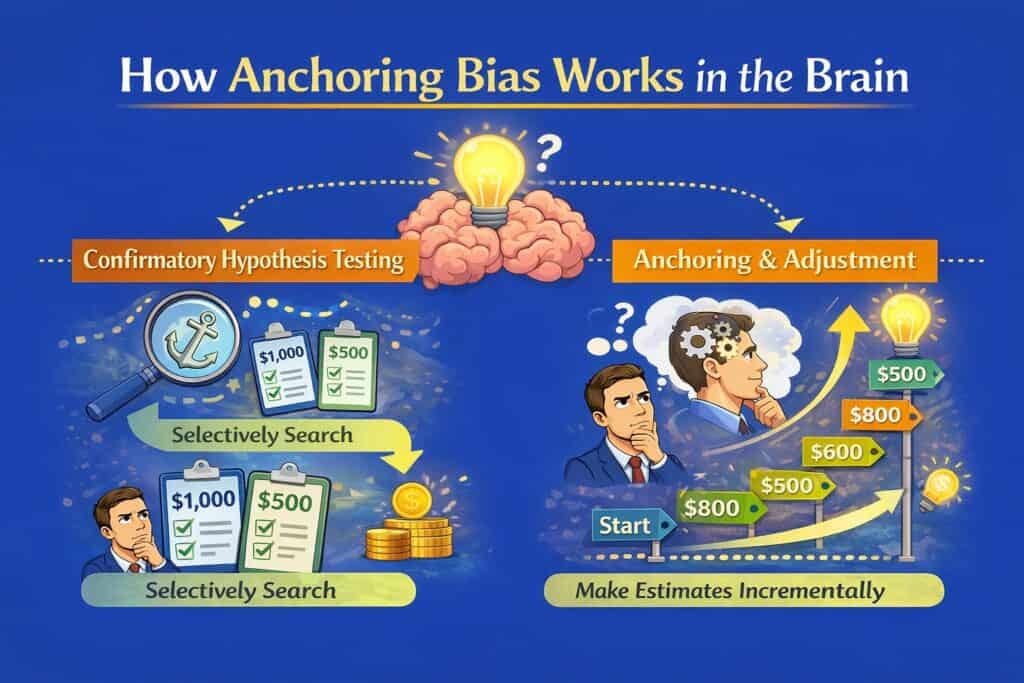

Psychologists explain how anchoring bias works in the brain through two main theories:

- Confirmatory hypothesis testing

- Anchoring and adjustment

Neither of the two requires you to be careless or uninformed, only human. You’d better be sure you understand that part first.

The first major cause of anchoring bias is confirmatory hypothesis testing. It occurs when an external anchor is presented, and the mind immediately treats it as a candidate and begins to selectively search for information that would make that value seem reasonable.

When the anchor is high, people are more likely to recall high-supporting information. When the anchor is low, the opposite occurs.

In any case, you produce estimates that drift toward the initial value even when the anchor is explicitly described as random or irrelevant.

The second mechanism is anchoring and adjustment, and this one doesn’t need an external trigger at all. When no anchor is given, people generate their own from intuition or partial knowledge.

That internally generated estimate is the anchor, the reference point from which adjustments are made incrementally.

Adjusting away from any anchor, external or internal, requires cognitive control that we don’t have much of.

So, people tend to stop adjusting once the estimate feels plausible rather than when it is maximally accurate.

Common Mistakes Influenced by Anchoring Bias

Anchoring bias leads to a slow drift in thinking, such that it leads us to overweight early information and underweight later evidence.

Researchers and those directly dealing with data anchor just as reliably as laymen. They are only better at justifying their conclusions.

Even though the reasoning may sound believable, the bias has not been eliminated.

So, in research peer review, or student grading, early impressions can lead to incorrect judgments of the subsequent information.

Look at retail. It is very common for us to overvalue discounted prices because when compared against the inflated “original” values, sale prices look good enough.

We make the obvious mistake of not comparing the discounted prices with those of alternatives to confirm if it really is discounted.

And then we end up spending more than intended. Of course, we do, because that initial price exposure recalibrates our definition of affordability.

People who know about anchoring bias trust their judgments more since they assume that insight protects them. It unfortunately does not, unless you actively put efforts into deliberate counter-anchoring.

Strategies to Avoid Anchoring Bias

You can not eliminate anchoring bias entirely. It simply is not possible because anchoring is an automatic, largely subconscious process.

Our goal is not avoidance in the absolute sense, but damage control, i.e., reducing how much the anchor gets to decide before you notice it is there.

One of the most reliable ways to weaken anchoring is to deliberately generate reasons why the anchor is inaccurate. It forces your brain to retrieve information that runs against the anchor.

Research shows that when people are prompted to argue against an anchor before making their own estimate, the anchoring effect is reduced.

You could also try to delay your exposure to anchors. Once an anchor enters awareness, it cannot be unseen.

So, researchers, for example, should form their own independent estimates before they get to review prior literature. For pricing and negotiation, too, you should decide your range before you hear the other side’s number.

The practice of multiple independent starting points is also related to delaying your exposure to anchors. You could dilute the effect of an anchor by simply thinking of 3-4 different starting points and trying to justify each with different reasons.

Truth be told, it is not too easy for a brain already under the effect of an anchor to counter-anchor and think of alternatives. You do better if you discuss things with someone or use an AI tool to your advantage.

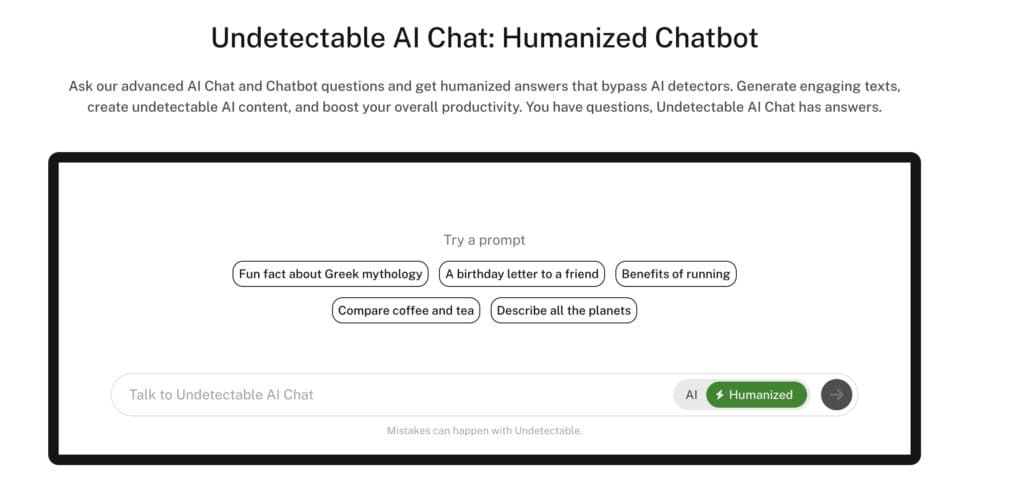

Undetectable AI’s AI Chat, for instance, can be used to deliberately search for reasons why an anchor could be wrong.

You just need to explicitly prompt the system to argue against the anchor, and that’ll broaden your thinking, too.

Explore our AI Detector and Humanizer in the widget below!

Final Thoughts

Since anchoring is a form of cognitive bias, it happens at a subconscious level.

Of course, it is difficult to interrupt what’s not in your conscious awareness unless you make a deliberate effort to do so. We are naturally wired to think this way.

And although it is very efficient to make fast decisions based on the first available information, it is also exploitable. Retail pricing works around anchoring bias.

Most of the time, we fall for the ‘so-called’ sale prices without realizing what we got wasn’t even worth the price. The cost is so much higher in data-heavy work.

Relying on your mind alone to counter an anchor is also not the best approach because that same mind is already under the anchor’s influence.

It’s best to talk through decisions with someone else without revealing your starting info, or use Undetectable AI to challenge the anchors. This is how you can shift your judgment back toward evidence.

Check out Undetectable AI today.